Chapter 4: Are we alike or unlike?

![]()

Stefan Hlatky

(This article was prepared as part of an 'exhibition' about the human being and the worldviews of human beings held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1980. Its introduction has been left as it stands for the sake of historical completeness. Translated by Philip Booth. Original Swedish version can be found at http://hem1.passagen.se/lanor )Contents for this Chapter:

Part I What is philosophy?

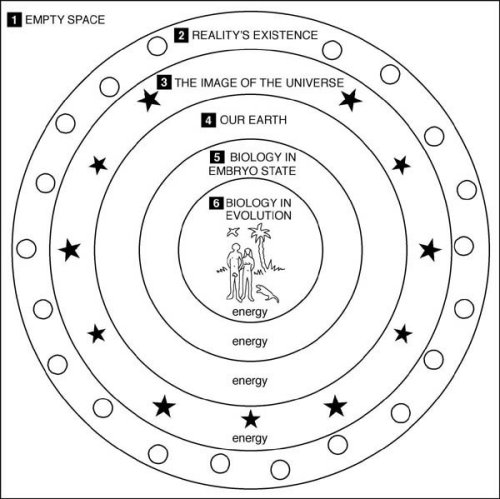

The whole and the part; the need for truth and mental health; the two parallel cultures; the problem of dissemination; the difficulty that led to errors; natural science's view of philosophy; technology becomes an end in itself and philosophy is dismissed; Energy and Matter; The Organic View of Unity: the cause 1. Empty space; 2. Reality's existence; 3. The image of the universe; 4. Our Earth; 5. Biology in embryo state; 6. Biology in evolution

Part II Historical background

The great cultures: background; the cause; the human being; meaning; social guidelines

Natural science: the historical background; the cause; the human being; meaning; social guidelines

Introduction

Introduction

At the end of the 1960s the Hungarian-born lawyer Stefan Hlatky put forward a philosophical theory about the existence of God which he called the organic view of unity. He arrived at his theory by applying to the philosophical domain the findings of natural science concerning the relationship between energy and matter. He was thereby able to throw new light on the age-old philosophical problems.

The basic idea of Hlatky’s theory is that the whole reality is a living existence, an organism, that is conscious of itself. We have its same quality of consciousness and are part of this conscious existence in a similar way to the way cells are part of our body. Existence itself, i.e. God’s and our own permanent existence – the Being – is not available to our senses. What we perceive with our senses as the universe is like a ‘hologram’, a moving, three-dimensional image- or energy-projection.

The exhibition aims to show that – with the help of modern natural science – the shortcomings of the old philosophies can be corrected, and we can arrive at a completely logical understanding of the situation of the human being.

In Part I the exhibition presents the organic view of unity. Part II describes the basic characteristics of the five major world religions and of science, and outlines their respective standpoints in relation to the basic questions of philosophy:

THE CAUSE What is the original cause? MEANING Is there a superordinate meaning? THE HUMAN BEING What about us is perishable, what permanent? SOCIAL GUIDELINES How do we organize a society that is satisfactory for everyone?

Hlatky’s aim is not to create a new society or to introduce a new philosophy. It is rather to try and break the state of conflict and resignation that exists in relation to questions about life and society, and through objectivity and logical reasoning to bring about a unification of philosophy, a unification that accords with the new findings of natural science as well as with the basic ideas of the old cultures.

WHAT IS PHILOSOPHY?

The whole and the part

The whole and the part

As far back in history as one can see, humans have been interested in the question of identity – that is, in understanding themselves as a part of the whole, a part of the whole reality. Understanding this was regarded as a prerequisite for understanding the meaning of the whole of life, if it has a meaning.

What we see of the universe are stars and planets dispersed in space apparently without connection, and therefore the question always arose as to whether there is an invisible whole behind the multiplicity. This question has led to two opposing hypotheses. The one is that there must exist a God who has created our fragmented, perishable reality and is outside it and separate from it. The other is that our perishable reality must have a permanent form that exists as an indestructible connected unity beyond the range of our senses. This indestructible reality has been given different names: ‘the being’, ‘the permanent being’, ‘the permanent order’.

The need for truth and mental health

The need for truth and mental health

It was already considered in the oldest known cultures that this philosophical interest – the interest in the invisible whole and the meaning of life – is a distinct need, the need for truth, which categorically distinguishes humans from animals. People were conscious of the fact that we are not compelled to meet this need, whereas, by contrast, we cannot escape the physiological needs that we have in common with animals. Since the need for truth is not forced in the same way, human beings can easily forget it. This is the problem of so-called ‘free will’: humans can choose to meet the need or to ignore it.

The psyche was taken into account in the oldest cultures as much as it is today. The starting-point of thinking then, however, was that a contradiction-free understanding of the whole of life, of the whole truth, and, arising from that, an experience of universal citizenship, are as important for mental health as fresh air, pure water and nourishing food are for physiological health. A life in which the human being’s need for truth is satisfied was denoted in different cultures by different names: wisdom, individuality, bliss, eternal bliss, righteousness, peace of mind, freedom, salvation, complete consciousness, cosmic consciousness, God-consciousness, love-consciousness, etc. Of course, the meaning of these concepts could vary, depending on what conception of the whole was held.

The two parallel cultures

The two parallel cultures

On the basis of this view of the human being, a categorical distinction was made between two different cultures. One culture, the ‘worldly’ culture – in today’s terminology, the technological culture – dealt with the ability of humans to acquire knowledge and to explore and direct ‘this world’, the visible, perishable world with which we have a tangible, objective relationship. The other, the ‘philosophical’ (or spiritual) culture, dealt with the invisible, permanent reality behind the visible world and beyond our influence.

1. The worldly culture and the question of power

The worldly culture’s aim was to cultivate and preserve all the skills needed by humans to cope in the best way possible with their environment, with regard to physiological needs, reproduction and the question of territory – that is, with human beings’ existential needs. This culture dealt with everything to do with power, i.e. action, strength, skilfulness, ownership, knowledge, arts and technology, as well as the acquisition of so-called supernatural (parapsychological) or magical (psychic) powers and skills.

2. The philosophical culture and the question of belief

The philosophical culture was organized cooperatively with the aim of cultivating and preserving the specifically human ability to use logical reflection to work out, understand and live in consciousness of the whole truth. This culture’s primary goal was, starting from the visible, to arrive at a logical theory of the invisible original cause of everything. It was understood that, in relation to the question of the original cause, it is only possible to work with hypotheses and theories. The whole problem was called, therefore, the question of belief. The aim from the beginning was to reach a clear belief that was completely anchored in reality, so this search was not to be given up until a hypothesis that accorded with every experience had been found.

The problem of dissemination

The problem of dissemination

It was whenever anyone succeeded in arriving at a tenable and contradiction-free theory that the hardest problem for the philosophical culture began. This was the problem of ensuring the general uptake of the theory, which required that the theory be disseminated and taught. The real benefit obviously comes when several people agree about a philosophy and they all strive to maintain that agreement on the basis of logic. The next important step was to establish the theory as part of general upbringing. It is necessary for children to obtain clear and logically coherent answers to the natural, philosophical questions that arise as they learn to speak, and for them thereby to acquire in a reality-anchored* way the whole theoretical reality of ideas that functions as a human being’s ‘own’ reality. This created the need to harmonize the philosophical culture and the technological, ‘worldly’ culture, as well as the need to preserve the clarity of the theory for the next generation.

In this way different theories have since time immemorial been passed down the generations, via language, as answers to philosophy’s timeless questions. This passing down has continued without interruption, at first by oral tradition, then later also in writing. It has either been organized by priests or initiates around more or less authoritarian pronouncements – that is, in what we usually call religions – or it has taken place in freer forms, as for example within Hinduism; or it has gone on as a splintered search for the truth without being guided by philosophical ambition, as, for instance, in the numerous Greek schools in the centuries before the establishment of Christianity.

The difficulty that led to errors

The difficulty that led to errors

Judging by the evidence, people were conscious that it is clarity and logical coherence which give philosophy its general validity and power to convince – that is, give it a natural authority, which cannot be replaced by either ‘supernatural’ or ‘worldly’ authority. The fact there are few signs of this insight in all the mysticism, superstition and authoritarian belief of the past is due to many things, but above all to the difficulty of communicating the philosophy.

Before the advent of modern mass media and energy-driven means of transport, this difficulty was, practically speaking, insuperable. Not only were people geographically isolated, but there were great chasms between people as regards education and, linked to this, the use of language. Everything was based on dialogue, there were only a few books and few people could read and write. To convey a philosophy in its entirety while maintaining its clarity was for these reasons alone almost impossible. In order to reach the general public a good many simplifications and popularizations had to be made, and if the philosophy was to be preserved, it had to be bound to a belief in authority and to associated cult ceremonies.

Geographical separation contributed to cultures developing in different ways. Differences then created breaches, competition and enmity between cultures. In addition, popularizations often led to a loss of clarity in the philosophy within one and the same culture. As consciousness of the truth diminished, the leaders of the philosophical culture were forced to present the inherited teachings in an increasingly authoritarian, power-conscious way that was incompatible with the aim of philosophy. This altered the relationship between the representatives of the philosophical and worldly cultures. Natural cooperation came to an end, to be replaced by rivalry for power, and this brought with it further conflicts and breaches that benefited neither party. The result was deeper and deeper error, until some other culture would take over, or until people would see reason and would reconstruct the logic that had given the original philosophy its strength.

Natural science's view of philosophy

Natural science's view of philosophy

An historically unprecedented change took place at the end of the sixteenth century, starting in Europe. This was modern science. People began to pin their faith on the development of technical instruments, which they hoped to use to correct gradually the shortcomings of the old philosophies. The commitment to this approach soon became complete. It rapidly spread over the whole Earth when developments in printing and other mass media, together with various energy-driven apparatuses, created new possibilities for communication and the dissemination of knowledge.

At the beginning of this technological development it was regarded as natural that philosophy and technology should work together, and so both cultures were considered necessary. But it was acknowledged that science itself excludes philosophical speculations, because scientific discipline demands that the subjective, i.e. emotion or feeling, should not be taken into account. Scientists are allowed to concern themselves only with the objective, the measurable, i.e. ‘the movement of matter’ (which they have divided into organic – biological and inorganic – mechanical).

Technology becomes an end in itself and philosophy is discarded

Technology becomes an end in itself and philosophy is discarded

In recent centuries, however, the interest in the development of technology has led to the technological culture being developed as an end in itself. This began early in the 19th century, when the hope was cherished that the whole truth could be arrived at by the scientific method alone. At the same time, the philosophical culture – and thus the belief in a living cause – began to be pointed to as the reason for all humanity’s errors. And then, so that no one could question the purpose of this completely one-sided development of only one culture (the technological), the idea of God and the idea that life has meaning were discarded. The philosophical culture thus became totally excluded from upbringing and education.

From a philosophical point of view, the most important discovery modern science has made is that what we perceive with our senses as matter is not matter in the true sense, but only one form of energy among other forms of energy such as movement, light, heat, electricity, etc. This was already clear from Einstein’s famous formula of 1905, E=mc2.

It became possible a few years ago to illustrate more practically that what we perceive as matter really can be an illusion when three-dimensional images, holograms, were constructed with the help of laser-beams. The same thing can be illustrated even more easily using concave mirrors, as in the ‘Mirage’ on show in this exhibition. [The ‘Mirage’ consists of two semi-spherical concave mirrors placed one on top of the other to form a sphere, with the reflective sides of the mirrors facing inwards. The top mirror has a hole in the middle of it, through which one can place an object in the bottom of the formed sphere. The image of this object is then projected by the concave mirrors in such a way that the object appears to be located in the hole at the top of the sphere.]

The old cultures often understood about the relativity of sense-experience. There are clear references to the fact that what we see is an illusion, an appearance, and not reality’s actual existence (e.g. maya in Hinduism, or Plato’s cave simile).

They could not, however, describe their theories in the objective way that science can today, and therefore could not draw any clear conclusions about the structure of reality. In place of the modern theory that energy can change into different forms, they thought that matter could convert into different forms, from finer to coarser. From this idea came the notion of the various elements: earth, water, air, fire and ether.

It was imagined that two material realities exist alongside each other. One was regarded as consisting of ‘fine’, subtle matter, which is therefore invisible and intangible: for example, spiritual beings, souls, astral bodies, etc. The other, which we perceive with our five senses, was thought to be constructed out of coarser material, and is therefore visible and tangible.

Modern energy theory requires us to completely abandon the idea, still surviving within religions, that matter has various forms. We must not, however, then make the mistake that many scientists make when they reject the idea of matter altogether and instead conceive of energy, functions and patterns of functions, as the original reality.

Energy means power, activity, work. It cannot be found by itself, but only as a potential or active quality in something that exists. The fact that our whole visible image of reality is energy means that it is no more real than the previously mentioned ‘Mirage’-image, or the images on a TV screen. This also explains why everything we can see is perishable and destructible.

According to modern science, kinetic energy (c) can appear in potential forms (m). This creates what we think of as dead things. This ‘materialized energy’, which in ‘materializing’ becomes visible, cannot be the original cause of what occurs in reality. The cause, which has the ability to express continuously our whole image of reality, must be a unitary existence that is invisible and intangible as a whole but is in a material sense permanent.

Diagram 18: The cause. (The diagram should be imagined as a sphere. The numbers on the diagram refer to the numbered sections 1 to 6 below.)

Click to enlarge

The cause

1. Empty space

1. Empty space

Everything that exists occupies space. Thus empty space is ‘nothing’, in contrast to the existent, which is ‘something’. Unfortunately, empty space has often been thought of in the same way as the existent is thought of – that is, as a three-dimensional ‘something’. Democritus, for example, who introduced the atom theory and materialism, thought of empty space as being just as existent as atoms.

‘Something’ – an existent whole – can only be imagined as limited. ‘Empty space’, on the other hand, cannot be thought of as limited, and so the idea of ‘empty space’ leads to irrational notions of infinity. ‘Something’ can be discussed and understood. But to conceive of and understand ‘empty space’ is clearly impossible.

When we are trying to understand reality, we should therefore devote our attention to the existent. ‘Empty space’ should be seen only as space. Knowing how great a volume existence has, or how much space existence needs, is not essential. What is essential for the understanding of reality is its quality, that is, what nature or property it has.

2. Reality's existence

2. Reality's existence

Reality’s actual matter, that which is ‘something’, must be uniform and unchangingly permanent, independent of time. Time is as unreal a concept as empty space. The idea of empty space leads to one notion of infinity, whereas the idea of time gives rise to two notions of infinity – the past and the future. Existent reality cannot possibly have begun or come into being. Nor can it cease to be or vanish. This is because something cannot arise out of nothing, and what is cannot become nothing. By contrast, it is the nature of function, of all activity, that it begins, goes on for a while and ends. It is this that gives us the experience of time and the practical need to calculate time. Function cannot be permanent or exist in the way the existent exists.

Reality is always in the present and is always the same. It must as a whole be a living being, since only this can explain all the function that goes on inside it. The alternative is that reality is a dead object. But a dead object cannot do anything by itself. It cannot cause or control its own activity. Nor can it act meaningfully. If reality were a dead object, it would be unable to display the minutely connected order that we see it manifests. So if the function in the whole reality – what we experience as Nature – is activity in a living being, we must take as our starting-point, not science’s movement of matter, but ‘the movement of the senses’ – that is, emotion, feeling – if we are to understand the whole function.

It is everyone’s experience that ‘the movement of the senses’ is the basic cause of every activity that living beings express. ‘The movement of the senses’, which characterizes consciousness, is what we call feeling or emotion – that is, our ability to be qualitatively touched by creation. All scientific explanations are incomplete in the same way, because feeling is not measurable and so cannot be included in them.

The idea that the whole reality is a living, conscious existence brings us to the notion of ‘God’. This is the name given to the whole existence, and the same or similar name that all earlier cultures used to denote the original living cause. According to the organic view of unity we, in our capacity as experiencing conscious minds [parts], are parts of God’s existence [the conscious minds (parts) are represented by the circles in Diagram 19], which throughout its whole has the same nature as we have. The difference is that God’s experience of himself encompasses us, who are parts of his existence, whereas our experience of ourselves cannot encompass God, the whole.

However, because of our ability to philosophize – i.e. logically to reflect on and understand the original cause – we have the possibility of encompassing God in our experience in a convincing way. Given this conception of God’s existence, it is easy to understand the meaning of life, as seen from both our side and God’s. The full benefit of love requires mutual understanding between likes, and this we see as the greatest benefit that life offers. The same must also be true for God. Thus the meaning of both our life in creation and God’s life in the Being – which basically are the same life – coincide.

God cannot show himself or talk to us in the way we can talk to one another, because the whole cannot have the same relation to the parts as the parts have to each other. That is why the possibility of understanding God is offered to us in an indirect way through the whole image-projection. Thus it can be said that the image of the universe is God’s talking to us, which we, with our ability to think logically, can interpret and understand.

3. The image of the universe

3. The image of the universe

The whole universe is like a hologram, that is, like an enormous cinema film with three-dimensional pictures. It is not reality’s existence. The continuous shining of billions of stars in combination with the rotation of the Earth reminds us every night that we live inside a gigantic, three-dimensional body, which we experience from the inside. Everything in our image of reality is function. It can therefore begin and end and recur at certain intervals. That is why a scientific theory of the beginnings of the universe can be considered as having a realistic basis. But such a theory is still only a statement about the periodicity of the universe. Science offers no explanation of either cause or meaning.

4. Our Earth

4. Our Earth

Every morning the image of the universe is turned off for us by our sun when it starts to illuminate events on Earth. It is here that we experience conditions in reality at close quarters. This takes place partly through the exchange with our environment that the satisfying of our physiological needs involves us in, and partly through our life together with other biological creatures, which compose a unitary household that we call an ecosystem.

5. Biology in embryo state

5. Biology in embryo state

Since nothing in the ongoing image-projection can exist unchanged, but has to be renewed continuously, all life on Earth proceeds from a beginning to an end. We experience the beginning as a germ state, and this can easily create the belief that the beginning of life is contained in the seed. This in turn leads to the idea that the rest of reality consists of dead matter. Within Christianity the irrationality of drawing a boundary between dead matter and life was dealt with by the explanation offered in Genesis that God intervened directly to create everything living out of dead dust.

When Wöhler demonstrated in 1828 that there is no boundary between dead (inorganic) and live (organic) matter, this was interpreted as proof that there is no God. The mistake was then made of writing off the concept of a living cause and with it the entire philosophical culture, and the whole reality began to be regarded as fundamentally dead, as functioning mechanically.

6. Biology in evolution

6. Biology in evolution

All bodies develop from a seed state into a fully grown state, and exist for a certain time as an active part in the total ecosystem. In order for the whole continuous development to be maintained, there has to be the same rate of breaking down as there is of growth. Things are so ordered that the whole of Nature’s household is sustained by its eating itself up all the time. If one forgets that the ecosytem is a closed system, one can become stuck on the concept of evolution and believe that the whole system, with humans currently at its apex, aims at a further evolution towards unknown life-forms.

The fact that everything sheds its seed and thereby forms the starting-point for new generations has led in the past to the insoluble problem of what comes first: the chicken or the egg. Such insoluble problems – which are characteristic of dualistic thinking – arise when one tries to understand function, the perishable, as an object in itself. Nothing can be solved with dualism. One has to have the idea of one reality behind the dualistic reality we experience. With the chicken and the egg, there is an infinite regress, unless one has an original reality. Note that objective science cannot say how things come into, how they appear in, this reality.

All understanding requires that we associate a function with an existing source expressing that function, e.g. sunshine with the sun, birdsong with a bird. So if we are to experience reality in an ordered way and not just as a chaos of functions, we must have some kind of source, an experience of some form or some living being, for any function that we experience. We need associations with visible forms in order to be able to satisfy our existential needs and to relate to our surroundings.

Within philosophy, on the other hand, where it is a question of understanding the original cause, it is crucial to grasp that all these forms we see are useful illusory forms or images. But they are not existence itself, the permanent.

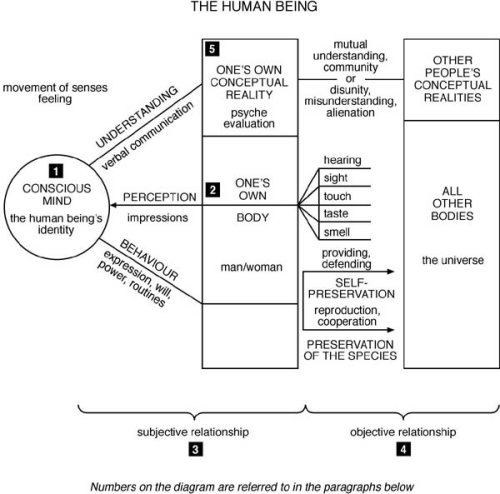

The human being

Diagram 19: The human being (Numbers on the diagram are referred to in the paragraphs in the text.)

Click to enlarge

[1] The human being’s real identity is the conscious mind [part], which is an inherent part of reality’s existence, conceived of as God’s existence (See Diagram 19). However, since existence itself is invisible and intangible, we can never demonstrate or prove our real identity objectively. We can only assume that we are a conscious mind on the basis of our subjective experience of being.

[2] Our body is a part of the whole energy-projection that we experience as reality’s image. Through our body the whole reality’s image is revealed to us at the same time as we, through our body, are indirectly revealed to others.

Everything in reality’s image is dualistic, bi-polar – e.g. light/darkness, warmth/coldness, positive charge/negative charge, living/dead, construction/destruction etc. This tells us that the image is not the permanent, unitary reality. This same polarity is expressed in the fact that the whole biological process that builds up Nature’s household is driven by the relationship between two sexes, male and female.

When the philosophical interest in understanding the permanent reality behind the perishable, bi-polar image is forgotten, human beings cannot come to an understanding of their real identity. They cannot then have feeling for others as like themselves, i.e. as having the same identity in the permanent reality, the Being. Instead, they begin to experience their identity in the dualistic image. This means they identify themselves with their body: either with its physical aspect, or with its mental aspect (their thinking or various skills), or with its sexual gender, interpreted as the source of emotional relationship (love). [I.e. the idea of relationships as involving ‘giving and receiving love’ (see, for example, Dialogue 3, ‘Can love be one-sided?’)] This creates alienation, on the one hand between the two sexes, and on the other between individuals on the basis of dissimilarities in appearance, abilities and intellect.

Nature-mediated consciousness

Nature-mediated consciousness

We are basically conscious of life in the same Nature-determined way that animals are. [3] This consciousness of Nature comes to us partly through the nervous system, as subjective impressions of the conditions in our body, and partly through our senses, as objective [4] impressions of the conditions in our surroundings.

Animals can only live in the now. They can only be aware of the ongoing impressions of current reality. They cannot ask themselves the question ‘Why?’, or be interested in background explanations, i.e. the whole truth. They simply follow their existential needs without being able to philosophize or reflect on the meaning of what they have to deal with. Thus animals are the species within Nature’s household that evaluate reality in determined, goal-directed ways. Individual animals follow the evaluation of reality that holds for their species as if programmed to do so – that is, without themselves knowing that this is what they are doing. The evaluating that animals do is thus not ‘individualized’, which is why Nature’s household functions so perfectly if we leave human beings out of account.

The human being's own reality

The human being's own reality

[5] The human being’s Nature-mediated consciousness becomes ‘individualized’ through the learning of language. When children learn to talk, they have to associate all their experiences with verbal symbols. In this way, each child develops their own language-dependent ideational or conceptual reality, which they must have if they are to be able to take part in general language communication.

It is through this ideational or conceptual reality that the human perspective arises. Thus humans have a double experience of everything. They have one experience that is practical, reality-based* – which they have in common with animals – and a second that is theoretical, memory-based. This conceptual ‘reality’ is our own to the extent that we ourselves create it, cultivate it and bear responsibility for it. Thanks to it, we can communicate all our subjective and objective experiences to each other. This opens up the possibility for us to understand and enjoy mutuality through being able to recognize our own experience of reality in others. We can then also work out the needs of other species and what their experience of reality, based on those needs, is.

In this way, all humans become conscious of the global unity of need-governed Nature, that is, of the subjective likeness of every living thing, behind the absolute objective unlikeness when viewed practically (it is not possible, for example, to find two oak leaves that are completely alike). [As Hlatky puts it, we are 100% alike and 100% unlike.] The discovery of mutuality makes it possible for us to enter into the experience of others. To the extent to which we can recognize our needs and problems in other living beings, we can acquire the same feeling for their lives as we have for our own.

This is how, alongside the Nature-mediated, objective understanding, there arises the subjective understanding that makes it possible for human beings to experience undivided love.

When this philosophical goal for the human capacity for reflection is forgotten, humans cease to experience their theoretical perspective on life as a (philosophically) objective perspective on the subjective – that is, on a living reality. Instead they experience it either as a subjective perspective on the objective – that is, on a non-living reality [this is a reference to pantheistic theories, see Dialogue 1]; or, as happens, for example, within scientific institutions, as a (technically) objective perspective on the objective (i.e a non-living reality).

In this way, human beings block the possibility they have of undivided love, because the unsolved philosophical questions then appear negatively as disturbances. They show up as a feeling of meaninglessness in relation to the perishability of everything, as anxiety in relation to death, and as disorientation around the question of identity, with this last creating a feeling of alienation. Alienation, indeed, is the absence of the Nature-given prerequisite for love: the experience of mutuality.

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

A short summary of the great cultures' and science's ideas as they relate to: the cause, the human being, meaning and social guidelines

The great cultures (background)

Hinduism (background)

Hinduism (background)

The word Hinduism is a geographical term that refers to the area around the Indus river in northern India. The word Brahmanism comes from the name of the Indian priestly caste, the brahmins. In modern times the terms Hinduism and Brahmanism are used interchangeably for the social and religious system that the majority of the Indian peoples profess.

The roots of Hinduism go back to about 3000 BCE. As a religion, however, Hinduism was not founded by a particular person, but grew continuously. It is also called the ‘eternal religion’ or the ‘eternal tradition’ in that it holds that human beings and incarnated gods – such as Rama, Krishna and Shankara – have appeared in every age in order to formulate the old truth in a new way.

Hinduism has no tightly constructed dogma. It carries out no mission in foreign lands and includes a multitude of gods, beliefs and ways to salvation.

All living beings in the universe are differentiated from birth by aptitude and duties. Within humanity there are also a number of different classes. At the top of this so-called caste system stand the brahmins, who perform sacrifices and teach the Vedas, the sacred texts. They are followed by the kshatriyas: warriors who uphold the order of society. Then come the vaishyas: farmers, craftsmen and merchants. These three highest castes go through a special initiation ceremony and are therefore called ‘the twice-born’. They have the right to study the Vedas by themselves. Beneath these three classes come the shudras: labourers who are supposed to serve the higher classes. At the bottom of the religious/social system are the pariahs: the untouchables, such as street-cleaners, etc. It is considered that the social organism will only be able to function if the different classes work together without conflict.

The Vedas are the oldest Hindu texts, dating from c. 1500 BCE and later. They contain among other things formulae and sacrifice-texts for religious ceremonies. The Upanishads, dating from c. 700 BCE and later, are philosophical texts about Brahman, the innermost being of the universe who is the basis of everything. The Bhagavad Gita, from c. 300 BCE and later, is a philosophical teaching poem that emphasizes devotion to a personal God.

The individual can choose from among the countless manifestations of the ‘highest being’ the one that satisfies their spiritual maturity. For the wise, it is a question of expanding their consciousness and recognizing that they are one with the original reality. If this appears to be too advanced, the individual may conceive of a personal God or creator, Brahma. Devotion to God then takes the place of wisdom. For the person who is not mature enough for this, God is represented by a statue in a temple. Rituals then replace meditation and righteous action replaces love.

Hinduism is still the dominant religion in India, where about 90% of the population are adherents. Worldwide there are 1.15 billion Hindus (2012).

Buddhism (background)

Buddhism (background)

Buddhism is a particular form of the Indian religion, Hinduism. The founder of Buddhism, Gautama Buddha, lived in India about 500 BCE

The name ‘Buddha’ – the enlightened one – refers to the enlightenment that he achieved sitting in meditation beneath a wild fig-tree. Here he obtained clarity about his earlier forms of existence, the reincarnation of other beings and the causes of suffering. The causes of suffering include: enjoyment of the senses, desire for life, and ignorance.

This insight freed the Buddha from further reincarnations and opened the way to Nirvana, a condition of eternal peace. Instead of entering Nirvana immediately, he began to preach his teaching about suffering and the overcoming of suffering.

The Buddha denoted certain parts of the Indian religion of that time as meaningless – for example, the caste-system, the custom of sacrifice, and the position of the brahmins (priests). He retained, however, the old Indian conceptions of karma and reincarnation. The Buddha recognized no personal God, but talked of an impersonal world-law.

The Buddha’s adherents were divided into two groups: lay people, living in families, who had a secular profession and observed five moral precepts; and orders, made up of monks and nuns, who lived in strictly regulated ways, in chastity and poverty.

The original core of Buddhism, Hinayana (the Lesser Vehicle) is aimed at only a small number of people. It is based on meditation and philosophically orientated insight. So there also gradually developed a popular form of Buddhism, Mahayana (the Great Vehicle) which puts the emphasis on active love of one’s neighbour, cult ceremonies and devout worship.

The texts in the Theravadas, which are said to render the Buddha’s word, were discovered about 200 years after his death.

Buddhism first spread throughout India and Sri Lanka. It later also took hold eastwards, in Cambodia, Korea, Thailand, Burma, Tibet, Mongolia, Vietnam and the Malay archipelago of Java, Sumatra and Borneo [now the Republic of Indonesia], and westwards, in Afghanistan and eastern Iran. In China, Buddhism achieved an importance equal to Confucianism. In Japan it was mixed in with the national religion, Shinto. Buddhism is followed nowadays (2012) by about 500 million people.

Universism (background)

Universism (background)

[The term 'universism' is attributed, by Helmuth von Glasenapp, in his book Die Funf Weltreligionen (Eugen Diederichs Verlag, Koln 1963) to J.J.M. de Groot.]

Universism, which is the system that is the basis of all Chinese thinking, originated in about 3000 BCE. Heaven, the Earth and humans constitute the unitary universe, which is governed by an all-encompassing law. There is a connection between Heaven above and the physical, psychological and moral life of humans on Earth.

The most important figures in Chinese thinking are Confucius and Lao Tse, who are both thought to have lived about 500 years BCE.

Confucius held the view that the human being’s task consisted in externally directed activity – in the fulfilling of his social role. He was a moral philosopher who promulgated norms both for the life of the individual and for the governing of the state. He revised and extended earlier traditions, collecting them in five so-called canonical books, among them the I Ching or Book of Changes. Confucius’s views were also passed on by his pupils in the form of dialogues and sayings. His teaching has in certain periods taken on the character of a state religion in China, with the idea of the emperor as Heaven’s representative.

Lao Tse saw the human being’s task as lying in internally directed contemplation, the aim of which is to experience the indescribable ‘Tao’ – the law of Nature and the eternal original source of all being. He is regarded as the author of the Tao Te Ching, the book about Tao. Confucianism and Taoism have existed side by side and have shaped social life in China for more than 2000 years.

Christianity (background)

Christianity (background)

Viewed historically, Christianity arose out of Judaism. It is best thought of as having at first been a Jewish sect. It had the same sacred texts as Judaism. Some generations after Jesus’s death the collection of texts that now constitute the New Testament was added to the Old Testament. The books of the Old Testament were written during the millennium before Christ, the New Testament between 60 and 100 years after Christ’s birth.

The centre of Christianity is the person, preaching, life, death and resurrection of Jesus. He was probably born in Bethlehem in ancient Judaea. It is thought that he occupied himself early in life with religious questions and acquired a deep knowledge of Judaism’s basic texts. When he was 30 years old he began his public activity, which lasted between one and three years. The success that Jesus had in his activity disturbed the Jewish authorities. They took particular objection to his saying in the Sermon on the Mount that the correct attitude is more important than a life led according to the letter of the law. The conflict with the Jewish authorities eventually led to his being accused of blasphemy and to his crucifixion.

Jesus’ disciples, however, insisted that Jesus had risen from his tomb, had shown himself to various people and finally had risen up to Heaven. The idea of a bodily resurrection meant that a special importance was given to the person of Jesus beyond his teaching. This had a great effect throughout history on the spread of Christianity. Paul later introduced the view that obedience to the law of Moses cannot absolve human beings. Only belief in Jesus Christ and his sacrificial death leads to salvation and eternal life.

Jesus rejected all demands that he should become an earthly king: ‘My kingdom is not of this world’ (John 18:36). He spoke of himself as the ‘Son of Man’, which in Aramaic is equivalent to ‘human being’.

Christianity, with its three main branches – the Eastern Orthodox, the Roman Catholic and the Protestant – has about 2.4 billion adherents today (2012). Europe became its centre, but it spread globally as Europeans explored new parts of the world from the end of the 15th century onwards.

Islam (background)

Islam (background)

Islam or Mohammedanism means ‘submission’, which refers to the fact that believers should submit to God’s will. Islam is closest to Judaism. Common features are that they distance themselves from polytheism and from the veneration of idols, and that they expect a Messiah and believe in the Day of Judgement.

The founder of Islam, Muhammad Ibn Abd-Allah, was born in 570 CE in the town of Mecca in what is now Saudi Arabia. At the age of 40 Muhammad came forward as a prophet of God. He saw himself as the last in a long line of prophets that included Noah, Abraham and Jesus. He emphasized that he was not divine, but only a human whom Allah had chosen for his mission. Muhammad had taken inspiration from both Judaism and Christianity when he began to develop his teaching.

The kernel of Muhammad’s religious message consists of sermons about the coming judgement. His sermons met with such strong opposition from the influential circles of Mecca that he and his followers were forced to leave and move to Medina. The sacred text of Islam is the Qur’an, a compilation of Muhammad’s teachings and revelations. The Qur’an’s content was not up to the standard of philosophically schooled thinkers, and so was interpreted symbolically. Islamic theologians and philosophers have diligently discussed how the belief in human free will relates to God’s omnipotence. The Qur’an acquired its definitive version soon after Muhammad’s death in 632.

Islam has about 1.8 billion believers (2012). It is spread in a belt across North Africa, eastwards through Central Asia as far as China, as well as down through India to the Malay archipelago.

The spread of Islam was closely associated in the beginning with the aspirations for power of the Muslim state. According to the Prophet’s original teaching, religion and state should form an indivisible whole. It is wrong to assert, however, that the conversion of a large part of the world to Islam occurred only with the help of the sword. From its very beginning Islam won many converts through the power of its ideas and through the social advantages it conferred.

Hinduism (the cause)

Hinduism (the cause)

In a philosophical sense the multiplicity of the external world is maya, an appearance. This appearance is a meaningful, permanently maintained reality-illusion. Behind this illusion there exists an original being – the absolute, Brahman. In the popular mind the original being is thought of as a supernatural personality which thinks, feels and behaves like a human being, even if it or he has many heads and arms and its powers exceed those of humans.

Just as wakefulness and sleep follow each other in humans, so, it is thought, there is a series of world-creations and world-destructions: Brahma-days, followed by periods of total rest, Brahma-nights.

Dharma, the eternal law, expresses itself partly as the natural order – by rivers flowing towards the sea, plants developing from their seeds, etc., and partly as a social order for all living beings.

According to the widely held Samkhya philosophy, there is ‘primal matter’, which is in an undeveloped state when the world is at rest. The primal matter is made up of three constituents or ‘gunas’: sattva (lightness and light), rajas (movement and pain) and tamas (heaviness and darkness). During the rest period these three gunas are in equilibrium, but at the world-creation they begin to interact at the initiative of the original being. First there arises the finer matter and then gradually all the coarser matter, and together they form the ‘world-egg’. The original being penetrates and fertilizes the egg and releases out of itself the creator-god, Brahma, to establish the world according to the eternal law, dharma.

The original being expresses itself in the form of three figures: Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva – a trinity that represents the original being in its functions as creator, sustainer and destroyer of the universe.

'In the beginning, my dear, this [universe] was Being alone, one only and outside this, nothing. Some say that in the beginning there was non-being alone, one only and outside this, nothing; and from that non-being, being was born. Aruni said: 'But how, indeed, could it be thus, my dear? How could Being be born from non-being? No, my dear, it was Being alone that existed in the beginning, and outside this, nothing. It (Being, or Brahman) thought: 'May I be many; may I grow forth.' [...] So He created the universe out of himself, and when He had created the universe out of himself, He went into every being. Everything which is has its self in Him alone. Now, that which is the subtle essence - in it all that exists has its self. That is the True. That is the Self. That thou art, Svetaketu.'

(From the Chandogya Upanishad)

Buddhism (the cause)

Buddhism (the cause)

Buddha does not deny that there are greater or lesser gods, but none of them is omnipotent or has created the universe. Even the highest, Brahma, is subject to the eternal law of change. This law governs him, just as the law of day and night, summer and winter, death and reincarnation, governs the world of life on Earth.

All phenomena in our world are perishable. There are no eternal material atoms, no original substance and no immortal souls. The process of the world has neither beginning nor end, and there is no boundary to the world’s space. A series of world-creations and world-destructions is assumed and, following from this, it is assumed that there exists an infinite number of world-systems.

Humans and the world they experience consist of countless factors, ‘dharmas’. Dharmas do not arise and vanish by chance, but are subject to strict regulation by law. They constitute the infinitely numerous forms of expression of the world-law, which manifests itself partly in the purposeful construction of the cosmos and partly also, through karma, in the moral order of the world.

Examples of dharmas are: earth, water, air, fire, life-force, perceptions, consciousness. Everything that can produce an effect is called a dharma. They are best characterized as forces. Dharmas have existence for a short time and then disappear. Their appearance depends on the presence of other dharmas, in the way that the appearance of a plant presupposes that there are a seed, soil, moisture, air, etc. The only dharmas that are indestructible and not dependent on other dharmas are empty space and Nirvana.

'The perfect person does not concern himself with the cause of the world, nor does he regard the present as temporally fixed, or fix his heart on rebirth in a special sphere.'

(From Purabheda Sutta)

'There is, monks, an unborn, unoriginated, uncreated, unformed. If, monks, there were no unborn, unoriginated, uncreated, unformed, there would likewise be no escape from the born, originated, created, formed.'

(From Udana)

Universism (the cause)

Universism (the cause)

The whole universe is seen as a giant organism in constant transformation, in which the different parts act on one another the whole time. The question as to what or who is the cause of these events is not clearly answered, but the main view is that it is an impersonal god-principle, alternately called ‘Shang Ti’, ‘Heaven’ or ‘Tao’.

Shang Ti – the ruler above – is at Heaven’s fixed point, the polar star, and observes all the events in the world. He is the originator of everything that happens, but is himself inactive. He has, however, no qualities that could allow any emotional relationship with humans. Shang Ti is foremost a personification of the order that manifests itself in Nature.

Tao means ‘way’. It is seen partly as the law of Nature and partly as the original being. Tao’s upper side is characterized by substance, essence, which is beyond our imagination and can only be intuited. Tao’s under side is characterized by its involvement in the world of the senses, which can be the subject of human investigation.

Out of the polar division of Tao into Yang and Yin – the three forming a trinity – emerge Heaven and Earth. Heaven is a masculine Yang-being and Earth a feminine Yin-being.

Yin and Yang in cooperation bring forth the seasons of the year and the organic world, which then reproduces itself with the help of seeds and seminal fluid. Heaven – Yang – is soul and is in movement. Earth – Yin – is body and is at rest.

'XXI

In his every movement a man of great virtue

Follows the way and the way only.

As a thing the way is

Shadowy, indistinct.

Indistinct and shadowy,

Yet within it is an image;

Shadowy and indistinct,

Yet within it is a substance.

Dim and darkà

à From the present back to antiquity

Its name never deserted it.

It serves as a means for understanding how everything came to be.

How shall I understand that things are like that with everything that is called beginning?

By means of this [the way].'

(From the Tao Te Ching)

Christianity (the cause)

Christianity (the cause)

According to the Old Testament, God is the only perfect being, who exists of himself from eternity to eternity. God is, furthermore, unchanging, and the universe and all that is in it is dependent on him.

God is a personal spirit-being, who is boundless, omnipresent, omniscient, all-wise and omnipotent, the creator of the world and originator of its order, and the world’s law-giver and judge. In the Old Testament God is described as omnipotent, ‘the Lord’, who rules over his creation and punishes and forgives humanity. In the New Testament Jesus speaks of God as ‘the Father in Heaven’ who loves humanity. In his teaching about God he emphasizes God’s goodness: ‘There is none good but one, that is, God’ (Matthew 19:17).

According to the usual interpretation, which is based on the story of creation in Genesis in the Old Testament, the world has been created by God out of ‘nothing’. The world is created in time, i.e. before the creation of the world only God existed. God sustains and rules the world. He guides it with mercy, wisdom and power according to his purpose.

In the New Testament the creation is described differently. Here the Greek logos, ‘the word’, is talked of. ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made’ (John 1:1-3).

The Christian church talks of God’s Trinity – the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost – but emphasizes monotheism, i.e. the belief in one God. Jesus is regarded as identical with the Son.

'1. In the beginning God created the heaven and the Earth.

2. And the Earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

3. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

4. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

5. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.'

(Genesis 1:1-5)

Islam (the cause)

Islam (the cause)

Allah is an eternal, unique being who was neither born nor conceived. He is the creator of everything and the omnipotent ruler of the universe. Allah is invisible, without form and not bound to any place. Seven properties belong to his existence: life, knowledge, sight, hearing, will, omnipotence and speech.

Only Allah can, in the absolute sense, act out of himself. Everything living and lifeless is dependent on him and subject to his will. It is he who brings forth everything. He is also the originator of all good and evil deeds. He is not bound by any norms: ‘He pardons whom he will and punishes whom he pleases’ (Qur’an, Surah 3). In Islam there is no concept of an evil force independent of Allah. What appears to us as lawfulness has to do with the fact that Allah generally allows Nature to follow a determined course. But if Allah wishes to, he can do away with this course of Nature at will.

The world has been created from nothing by Allah’s command ‘Be!’ According to the Qur’an, he created seven heavens and seven earths. The heavens lie in storeys on top of one another. A usual formulation is that above these heavens are a further seven seas of light and finally Paradise itself with its seven compartments. Beneath our Earth are six hells.

The creation of the world was completed in six days. In the first days, Allah created the Earth; in the following days, he created everything that exists on Earth; and in the final days, he created the heavens.

The Qur’an distances itself strongly from the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, the ‘Godhead-in-Three’.

‘In the Name of Allah, the Compassionate, the Merciful

Allah is One, the Eternal God.

He begot none, nor was he begotten.

None is equal to Him.'

(From the Qur'an, Surah 112)

The great cultures: the human being

Hinduism (the human being)

Hinduism (the human being)

The world is peopled by an infinite number of living beings: plants, animals, human beings, spirits, demons and demi-gods. Between humans and animals there is a difference only of degree. Each being consists of a spiritual soul – atman – and a more or less material body.

The soul, which exists timelessly, without beginning or end, continuously establishes new bodies of different kinds, in accordance with karma, the good and evil actions it has performed. During its migration from the dead body to the new body the soul is surrounded by an invisible body made out of ‘fine’ matter, which contains the organs for perception, memory, imagination, will, etc. During the night, in the state of deep sleep, the soul enters the ‘All-One’ and returns on waking to the world of multiplicity.

Human beings in their capacity as souls are imperishable, but they have been placed in the perishable, material world that does not have real existence. Because they believe themselves to be their perishable body, they experience fear and suffering. Only when they free themselves from their ignorance about the character of the material world, when they challenge their suffering and ask questions about the nature of the Absolute, Brahman, do they begin to be humans in the real sense, i.e. make use of their human ability.

The caste-system with its ranking order only has validity for the existence that is related to the world, and is connected to karma, the consequences of actions in earlier existences. However, everyone, irrespective of which caste they belong to, can attain spiritual perfection or salvation. But then there is another ranking order which indicates how near to, or how far from, salvation any individual is. Salvation – becoming free from the cycle of reincarnation, samsara – can only be attained by eradicating one’s ignorance and by renouncing one’s desires.

'Know the Self to be the master of the chariot; the body, the chariot; the intellect, the charioteer; and the mind, the reins.

The senses, they say, are the horses; the objects, the roads. The wise call the Self - united with the body, the senses, and the mind - the enjoyer.'

(From the Katha Upanishad)

Buddhism (the human being)

Buddhism (the human being)

All the parts of the world-system up to Brahma’s heaven are subject to a periodically recurrent appearance and destruction. At the beginning of our world’s appearance a situation of Paradise rules on Earth. Humans are sexless light-beings who need only subtle food and do not need to work.

Over time desire arises, and this fall of man leads to people beginning to use more substantial food, to cultivate the earth, to build houses and to choose a king. Thus arise the castes. The moral decay continues for thousands of years, ending in a great part of humanity taking each others’ lives in a great war. Some peaceable people, who have retreated into the woods, now lay the foundations for a new and better culture.

There is no indestructible soul, but in its place is a changeable number of elements enveloped in a physical body. These elements do not stop with death, but continue on the other side to effect the break-up of the physical body and to create the basis for the life of a new individual, who is heir to the deceased’s good and evil acts.

What seems to us to be a unitary personality is a cluster of dharmas of various kinds that have combined into an apparent whole.

The connecting link between the old and the new existence are desire, the impulses of will and the thirst for life. Reincarnation can occur in any of the universe’s myriad worlds. Where and when reincarnation is to take place people themselves determine by their actions – karma. Karma is a comprehensive balance-sheet kept by the book-keeping device inherent in creation’s lawfulness.

The starting-point of the path to salvation is reached through the insight that everything earthly is perishable and full of suffering. By refraining from evil, by performing good deeds, by purifying one’s heart and by clarifying one’s thinking through meditation, one reaches enlightenment and Nirvana by degrees, and reincarnation comes to an end.

Twin-verses:

'All that we are is a result of what we have thought. It is based on our thoughts, built up on our thoughts. If anyone speaks or behaves with bad intention, suffering follows him just as the wagon-wheel follows the ox's foot.

All that we are is a result of what we have thought. It is based on our thoughts, built up on our thoughts. If anyone speaks or behaves with good intention, happiness follows him like a shadow which never leaves him.'

(From the Dhammapada)

Universism (the human being)

Universism (the human being)

The human being is the result of cooperation between Heaven and Earth. Heaven gives the spiritual, subtle Yang-element and Earth gives the coarse Yin-element. The soul is seen as an individual being that can continue to exist for a shorter or longer time after its separation from the body. The strong emphasis on reverence for the spirits of ancestors is based on the idea that the deceased are in some way still present.

Harmony rules in the universe, and so this must also be the case for humans. Hence humans are seen as good by nature, while all the evil in them is the result of inadequate insight. In order to avoid misconceptions that disturb the harmony, humans must acquire insight and knowledge by studying the past and by imitating moral examples.

The belief of the masses, however, is defined by the idea there are countless good and evil spirits, which float around everywhere and can bestow blessings or cause harm.

'XVI

Knowledge of the constant is known as discernment.

Woe to him who wilfully innovates

While ignorant of the constant,

But should one act from knowledge of the constant

One's action will lead to impartiality,

Impartiality to kingliness,

Kingliness to heaven,

Heaven to the way,

The way to perpetuity,

And to the end of one's days one will meet with no danger.'

(From the Tao Te Ching)

Christianity (the human being)

Christianity (the human being)

According to the Old Testament story of creation, God first created humans in his own image. After that he formed the human body out of the ‘dust of the ground’ and breathed the breath of life into it.

First God created Adam, the first man. He then created Eve, the first woman, from one of Adam’s ribs. They lived a blissful life in Paradise. They had perfect control over their sensuality, i.e. they had no physical desires that were at variance with the ‘spirit’, nor were they ashamed of their nakedness.

Before God formed humans on Earth, there also existed, created by God, invisible, personal spirit-beings endowed with understanding and will, who can take on a visible body for particular purposes. These beings, who are God’s servants, are called angels.

The likeness of the human to God consists in the fact that the human, in contrast to the animal, is endowed with an immortal, spiritual, intelligent soul and possesses free will. The spirit, the nature of which is eternal, can exercise control over the life of the soul. The spirit is the centre for the ethical, moral and religious life of the human. The soul exercises control over the body.

The idea of reincarnation existed in Christianity, but was abolished at the Church Council of 553CE.

From the moment that God created the angels, they possessed complete knowledge of God. But God put them to the test. One group of angels did not pass the test. Blinded by arrogance, they deserted God and tumbled down into the underworld. Although they can leave their abode from time to time in order to tempt humans and to lead them astray into sin, they cannot do anything unless God allows it. The will of the ‘devils’ is no longer free; they can only choose between different evil deeds.

One of the fallen angels, Satan, entered Paradise by taking up dwelling in a serpent. He seduced Eve into eating fruit from the forbidden tree, the tree of knowledge. Eve then persuaded Adam to eat the forbidden fruit. Because of this sin of eating from the tree of knowledge, they were driven out of Paradise. The sin was inherited by all Adam’s descendants.

'26. And [God] hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the Earth, and hath determined the times before appointed, and the bounds of their habitation;

27. That they should seek the Lord, if haply they might feel after him, and find him, though he be not far from every one of us:

28. For in him we live, and move, and have our being; as certain also of your own poets have said, For we are also his offspring.'

(Acts of the Apostles 17:26-28)

Islam (the human being)

Islam (the human being)

Living beings are divided into various categories. The most perfect are angels, whom Allah created out of light. They are sexless beings who neither eat nor drink. The most important angels are Gabriel, who for twenty-three years communicated the content of the Qur’an to the Prophet; Michael, who bestows rain and food; and Izrail, who is the angel of death.

Allah created the original human, Adam, from clay and water and breathed the breath of life into him. After creating Adam, Allah caused the whole of mankind to arise out of Adam’s spine and to make a declaration of faith. He then led them back again into Adam’s spine and collected the souls in a shrine on his throne. There they wait until the time comes for their birth, when they can be united with the bodies allotted to them. With death the soul and body are separated, to be united again in the resurrection on the Final Day of Judgement.

Shaitan (Satan) or Diabolos was originally an angel. He was ejected from Paradise because, out of pride, he would not prostrate himself before Adam, who had been created from clay. Together with his under-devils, he tries to entice humans to do evil, until he himself will be annihilated on the Day of Judgement.

The first human couple were Adam and Eve, and the same stories are related about them as in the Bible. Humanity was not burdened with original sin by the Fall, because Adam repented and obtained forgiveness.

Adam was the first prophet to instruct humanity on the basis of divine revelations. Other prophets followed him, Muhammad among them.

'Does there not pass over a man a space of time when his life is a blank?

We have created man from the union of the two sexes so that We may put him to the proof. We have endowed him with sight and hearing and, be he thankful or oblivious of Our favours, We have shown him the right path.

For the unbelievers We have prepared fetters and chains, and a blazing Fire. But the righteous shall drink of a cup tempered at the Camphor Fountain, a gushing spring at which the servants of Allah will refresh themselvesà'

(From the Qur'an, Surah 76)

Hinduism (meaning)

Hinduism (meaning)

In the Bhagavad Gita it is said that the purpose of all living beings – i.e. the purpose of the parts that inhere in the wholeness – is to serve ‘God’s highest personality’. This service also gives joy and satisfaction to those inhering parts.

The teaching about karma and the transmigration of the soul is central. In the worldly existence the aim is to obtain a good form of reincarnation through good deeds. But even the happiest form of existence comes to an end some time, so those who learn to recognize the transitoriness of worldly striving focus instead upon achieving permanent salvation. This salvation can be reached in different ways. One such way is through love and devotion (bhakti) to the personal Godhead, in order to be freed by its ‘grace’ from everything that binds one to the perishable world.

According to the truly philosophical schools, human beings must themselves, however, arrive at an understanding of the perishable nature of the material world, of maya. Through this understanding they can curb their suffering, thereby preventing new karma, and can destroy their karma from earlier existences. What is required is, on the one hand, insight into the unity of the Godhead and the soul, and on the other, insight into the dissimilarity between the soul (which is permanent) and what we call matter (which is perishable). This insight must not be merely theoretical, but must involve intuitive knowledge for which study of the sacred texts and regular meditation exercises are a necessary preparation.

When a person has attained this salvation or insight, their actions come to coincide with the will of ‘the highest consciousness’, and this has the effect of making them happy.

The situation of the saved person after death is described in different ways: sometimes as a merging into the Godhead, but more usually as a continued individual existence in a non-earthly life.

'I am the One source of all: the evolution of all comes from me. The wise think this and they worship me in adoration of love.vTheir thoughts are on me, their life is in me, and they give light to each other. For ever they speak of my glory; and they find peace and joy.'

(From the Bhagavad Gita)

'In reality you are always united with God. But you must know this. Beyond this there is nothing more to know. Meditate, and you will understand that spirit, matter and Maya (the force that unites spirit and matter) are only three different sides of Brahma, the Only Reality.'

(From the Svetasvatara Upanishad)

Buddhism (meaning)

Buddhism (meaning)

Buddhism is intended as a path to salvation for individuals. The well-being of the whole is a joyful consequence and a beautiful by-product of the right behaviour of the individual, but there is no original purpose for which the ‘wheel of the law’ is set in motion.

Life is suffering, because everything is perishable and even the happiest person is subject to illness, ageing and death. Suffering can disappear only if desire and the other passions that bring about reincarnations can be destroyed. This can occur only gradually over many existences. Progress towards salvation is stepwise: first the gross moral mistakes are removed from worldly life, and then, through spiritual asceticism, the finer forms of passion are also eliminated.

What leads to salvation is neither exaggerated self-torment nor surrender to enjoyment of the senses, but rather the middle way: a moderate denial of the world.

The path to the abolition of suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path: right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration.

When one has acquired complete freedom from passions, one has reached the goal. One is then a Buddha – a sublime, perfect human being. One still wanders, of course, upon the Earth, but with death one enters the eternal peace of Nirvana.

Compared with the world, which is in constant movement, Nirvana is a quiescent existence. For the wise it is the only true, blessed reality, which persists when all the perishable dharmas are away.

‘The greatest happiness that a man can imagine is the bond of marriage that ties together two loving hearts. But there is an even greater happiness, and this is to surrender oneself to the truth. Death will separate husband and wife again, but death will never do any harm to him who has united himself with the truth.’

(From Wedding Feast in Jambunada)

Universism (meaning)

Universism (meaning)

The big life-questions about the cause and meaning of everything are put in the background by both Confucius and Lao Tse. Confucius instead emphasizes behaviour, while Lao Tse stresses that Tao, the concept of the ultimate limit, lies beyond both words and silence.

Harmony with the cosmos, the universe, is the basis of a happy life. Therefore, the human being’s foremost endeavour must be to get to know the world’s process, so as to be able to conform to its order. An important aid in this is the I Ching or Book of Changes, the symbols of which are interpreted intuitively. In addition, astrology, number- and colour-symbolism and meteorological phenomena can be studied.

In their ethical attitude human beings must follow the lofty example of Heaven. Anyone who fails to follow the world-law, but strives for selfish goals, encounters misfortune.

In order to experience peace of mind and to gain insight, a person within Taoism can use meditation and contemplation in order to keep sense-impressions and consciousness of one’s own personality at bay and thereby reach a state of transcendence. There thinking becomes like a mirror for the ‘world-spirit’, and the person can experience the ‘highest bliss’.

In popular belief the deceased are rewarded in a Heaven or punished in a Hell – a notion, however, that is alien to the great Chinese thinkers.

'The Master said, A gentleman, in his plans, thinks of the Way; he does not think how he is going to make a living. Even farming sometimes entails times of shortage; and even learning may incidentally lead to high pay. But a gentleman's anxieties concern the progress of the Way; he has no anxiety concerning poverty.'

(From The Analects of Confucius, Book XV)

Christianity (meaning)

Christianity (meaning)

God’s purpose with creation is to make his perfection known to the created beings. The human being’s task, according to the Old Testament, is to honour and serve God in humility and obedience.

According to the account of creation in the Old Testament, the world is created for humans’ well-being. The Earth and the heavenly bodies, the animals and the plants have no purpose of their own, but exist only for the sake of humans. Humans occupy a unique position: they are the crown of creation, and everything that takes place in the world takes place for their sake.

According to Jesus, the aim of the human being’s life is to live in love of God and one’s fellow human beings.

Through the disobedience to God of Adam, humanity’s first ancestor, the whole of humanity became sinful and lost eternal life in Paradise. In the New Testament Paul introduces the idea that, because of original sin, humans cannot break the influence of evil by their own force. Freedom from sin can occur only through God’s grace, which God expresses by allowing his son, Jesus, to suffer a vicarious expiatory sacrifice for the whole of humanity. When a person believes in Jesus, there ensues a complete change of mind – salvation – so that the person renounces all sinful acts and can partake of eternal life.

As judge, God rewards all good and punishes all evil. The punishment in many cases is already carried out during life on Earth. When the soul becomes separated from the body through death, it is judged and receives payment for its actions. The righteous receive, according to their deserts, a greater or smaller share of bliss: ‘In my Father’s house are many mansions’ (John 14:2). Those who reject true belief go after death to Hell. There they undergo different punishments, in proportion to their sins.

'31. Therefore take no thought, saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed?

32. (For after all these things do the gentiles seek:) for your heavenly father knoweth that ye have need of all these things.

33. But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.'

(From Matthew 6:31-33)

Islam (meaning)

Islam (meaning)

The human being constitutes creation’s true aim. For humans Allah has spread out the Earth like a carpet and stretched the sky upwards like a roof. Animals and plants, too, have been created entirely for the sake of humans, to give them food and clothing, to carry their loads and to serve them in other ways.

To the question as to why Allah created the world, Allah replies with the following words: ‘I was a hidden treasure and I loved to be known, and therefore I created so that I might be known.’

The human being’s task is to submit to Allah and to obey his will as it has become known through the Qur’an.

Thoughtfulness is considered a form of piety, and knowledge and reason are described as what Allah created first of all.

On the Day of Judgement, Allah will allow the good humans to partake of the delights of Paradise and will make the evil ones suffer the eternal torments of hell-fire.

'But those who believe and do what is good - and we put no more on a soul than it can carry out - they belong to the kingdom of heaven and will remain there eternally. And from their hearts we shall remove all resentment and all worldly enmity.'

(From the Qur'an, Surah 7)

The great cultures: social guidelines

Hinduism (social guidelines)

Hinduism (social guidelines)

The caste order prescribes in detail what the members of each caste should do and what they must avoid. The system of rules is not general, but differs from caste to caste.

There are separate initiation rites for male members in the three highest castes. They have to learn, for example, secret ‘mantras’ (holy words), which they must repeat every day throughout their lives. Young brahmins leave their parents after the initiation and must learn ceremonies and study the sacred texts under the guidance of a teacher (guru).

According to one tradition, there are four life-goals: 1. fulfilment of duty; 2. wealth, material happiness; 3. sexual satisfaction; 4. salvation, freedom from reincarnation.

Fulfilment of duty refers to duties towards parents and the authorities, as well as to the kindness and helpfulness one should show towards other people. This social attitude, however, amounts more to a collecting of credits for the individual’s own sake than to a sharing in and sympathy for the needs and suffering of others.

Each individual’s fate is a necessary consequence of their actions in a previous life. Those who live a worthy life on Earth are reincarnated as a brahmin or as a warrior, whereas those who live an unworthy life are reincarnated as social outcasts, or as dogs or pigs, etc.

To help on the path to salvation, different exercises can be performed. These exercises are called yoga ‘union’ and take different forms. For example:

Karma-yoga (the path of action), which is based on practising good actions. Good actions do not lead to salvation itself, but are a necessary preparation for subsequent paths

Bhakti-yoga (the path of devotion to God), where the individual strives to be united with the Godhead through service, adoration and devotion, with, among other things, the help of songs and mantras that give expression to fervent love of God

Jnana-yoga (the path of knowledge), the aim of which is the achievement of understanding and, through understanding, the developed, real experience that the individual's innermost self is united with the divine Brahman.

'Treat others as you yourself wish to be treated.'

Krishna

Buddhism (social guidelines)

Buddhism (social guidelines)

Correct behaviour is governed by Buddha’s ten precepts, of which the first five hold for the believing laity:

1. Not to kill any living being (which is why Buddhists are vegetarians)

2. Not to steal

3. Not to lie

4. Not to be unchaste