Chapter 3: The organic view of unity

![]()

Stefan Hlatky

(This is the second part of an article prepared for an 'exhibition' held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1976, to present Hlatky's hypothesis. Translated by Philip Booth. Original Swedish version can be found at http://hem1.passagen.se/lanor)Contents for this Chapter:

What is religion?; what is the organic view of unity?; what counts as evidence?; science cannot lead to philosophy; distinguishing between philosophy and technology; the ABC of philosophy; God and the conscious mind; scientific research offers evidence; experience of life nowadays; experience of life in the future

For almost two hundred years there has been a pointless confrontation between theology and atheism. Innumerable naive forms of theological belief have been opposed by an anti-belief, atheism, that tries to hold a non-existent, and therefore unassailable, position between an irrational, absolute denial of all belief and an equally irrational, absolute belief in the future of technology û that is, in the ability of humans to be original creators. This pointless confrontation must end. It needs to be replaced on both sides by a philosophical attitude, in the original meaning of the word 'philosophical', namely 'reflection on the truth concerning the original cause of the changing and perishable reality we experience'. It is essential that this happen if we are to escape from the impotence that thinking has suffered from since its derailment in 1828. [See footnote 1, p.10.]

Theologians and religious groups need to recognize that they gain nothing by committing themselves to interpretations that they themselves do not understand and also, therefore, cannot explain.

The representatives of atheistic anti-belief need to realize that thinking is not a free-standing treadmill that can be turned at will for one’s own amusement or that of others, without the slightest consideration of what its natural purpose is. They must also realize that it is no solution in the long run to blame the psychological distress caused by disorientated thinking on the concept of God or on religions in order to bolster an argument for getting rid of these.

The belief in life, the belief in the living unity, and the religious thinking linked with that belief, are part of the innate human characteristic that distinguishes us from animals. If human language – the tool that religion uses to answer children’s questions about the meaning of life – is impoverished by having its role restricted to that of making only mechanical descriptions and connections, this will still not get rid of this characteristic. We must realize that the greatest conceivable offence against children is to prevent them from developing their innate feeling for the living unity of existence.

The fact that the Church has contributed to the situation by indoctrinating people with a superstitious theology is a separate issue. It is no solution to compound this by exploiting language in every way to parody tastelessly the human capacity for belief and the concept of God, the symbol of the living unity. This locks children exclusively into their ability to orientate technologically* to the world.

What is the point of a hate campaign against God? And can it be right to destroy a child’s belief in life and the love that goes with that belief by tying the belief, through language, to the idea of a meaningless, dead reality driven by chance?

With all their natural questions about life and reality, children constantly try to put a living image together. But the attempt is futile so long as it is the generally accepted practice in upbringing and education to gloss over their questions with a vague reference to the progress of technology. Technology offers only the mass production of data and ‘truths’ that relate to a dead, mechanical view of life. Given such ‘progress’, mental health can only deteriorate with each generation.

Technological progress since 1828 clearly exemplifies the 2,000-year-old saying: ‘For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?’ (Matthew 16:26, Sermon on the Mount). Technological progress is good for physical health and increases the yield of our physiological lives, but it cannot promote the psyche’s, the inner person’s, health. Mental health will inevitably deteriorate as long as we encourage children to have their thinking directed by a view of reality as dead and driven by chance, and as long as we deny the necessity of a God-based philosophy of life and any notion of the invisible unity of reality as living.

It may be true that the literal-minded, scholastic Church has lost the ability to interpret Christ’s teaching in the Sermon on the Mount. But it does not testify to greater talent to make cheap fun of that inability and glibly to ridicule the ethical problem addressed in the Sermon on the Mount, which each of us must face. An opposition that offers only aggression and abuse is simply being destructive.

The Greek word politik means political science, and the task of politics is to solve the problem of how we live together as this relates to our existential needs. In this sense, politics is necessary and of practical use. But the belief that humanity’s psychological problem can be solved by politics is a catastrophic mistake. It can only lead to further wars and to an increase in the lust for power and in competition and hatred between people.

What is religion?

What is religion?

All children realize that the senses are limited. So children are not satisfied, as animals are, by just their sensory experience of the environment. They explore and take an interest in everything, thereby demonstrating that, alongside their interest in satisfying their existential needs, they have the curiosity and the interest in understanding that are typical of humans. To begin with, this interest in understanding lacks direction. Children also need protection and care so that they do not harm themselves. Only when they have learnt to talk can they meaningfully begin to give expression to the human need to understand. They do this by asking adults questions about the causes of everything and about what cannot be seen or grasped with the senses.

This need and ability to understand the cause of everything is a natural, innate characteristic, and not an interest that adults create. The evidence for this is that all children, when they have learnt to talk, express the need, earnestly and with authority, in the form of a crystal-clear logic that often confounds adults and makes them feel embarrassed and inferior.

The word ‘religion’ comes from the Latin ‘re-ligio’, which means ‘to lead, tie or link back’, referring to the acquisition of language. When children learn to talk, they are inescapably drawn into – that is, led, tied or linked back to – the adults’ and previous generations’ conception of reality. Thus language functions as a mental inheritance, alongside biological inheritance.

The word ‘religion’ in its original meaning points to the collective responsibility we have for language. The adults’ generally established conception of the human being and of causality in reality is expressed in language, which thereby ties all children into this general conception. Children cannot challenge the adults’ conception in its entirety until they themselves become adults. So when the adults’ philosophy is confused, children lose as they grow up the logical, crystal-clear philosophical perspective they had at the beginning. This explains how mistaken ideas about fundamental philosophical questions can persist for hundreds of years.

The problem of identity culminates in puberty, when children encounter, through their experience of sexual maturation, the psychological problem of the relationship between the sexes. This combines with children’s realization that they must shortly take full responsibility for themselves, and provokes a sharp identity crisis. They are forced to undergo something akin to a new birth, in which they have to leave behind the insecure, unclear identity of childhood and assume a new identity. They have to try to be grown up, and to pretend like everyone else to be secure, lucid and mature. Like everyone else, they have to carefully hide themselves psychologically. They are ashamed that they feel a lack of identity, though this is a collective problem that we can only overcome together, and of which, if we should feel ashamed at all, we ought to feel collectively ashamed.

What is the organic view of unity?

What is the organic view of unity?

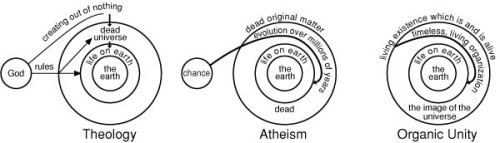

The organic view of unity is an initiative1 aimed at collectively and objectively testing the proposition that we and reality as a whole exist as a single, interconnected organism, a living body. The organic view of unity is based on the concept of one Nature as the expression of this whole – that is, on the concept of the universal unity of life. It thereby addresses the illogicality of the stance that both theology and atheism take in relation to the question of the original cause – which is to exclude the concept of the universal unity of life. They proceed instead from a concept of Nature as both dead and living.

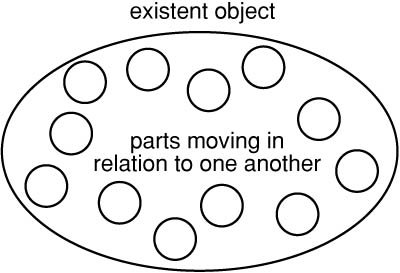

Theology and atheism themselves differ. Theology talks of an invisible, living being who created the world at the beginning of time and who has since had technical control over the ‘dead dust’ and the living organisms. Atheism does not accept the idea of God as the technically controlling cause, but sees ‘dead matter’ (or at least what our sight judges to be ‘dead matter’) as performing this role. So atheism in effect sees dead matter as the (dead) creator or God, which, it is maintained, has created us and all other living organisms over time with the benevolent assistance of chance (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1.

Click to enlarge

The question of the original cause – a fundamental philosophical problem that is absolutely crucial for humanity – has thus given rise to the most naive culture-clash in world history. This has been going on for almost two hundred years now and is on the point of destroying the ability of human beings to survive.

What counts as evidence?

What counts as evidence?

The evidence for the existence of an invisible reality is each person’s own experience that the sense of sight is limited. It is precisely because everyone knows that the ability to see is limited that everyone is interested in and thinks about the invisible. The reason humans can do this thinking already as children is that the capacity for reflection in humans is not confined to their existential needs, as it is with animals. Every person has the freedom, out of love for the truth, to philosophize, to reflect logically on humanity’s natural situation and on the cause and meaning of the whole creation. The demand for evidence, the demand that others should show what it is impossible for anyone to see, demonstrates that some people are willing to believe only in what they can see. By believing only in what can be seen, these people restrict the unrestricted ability humans have to deliberate on the basis of all their experiences of existence.

Science cannot lead to philosophy

Science cannot lead to philosophy

Scientific progress amounts to discovering more and more and thereby expanding our capacity to act in relation to the visible environment. Developing this capacity is both necessary and good. The mistake is to rely on this capacity alone and to believe that discovering more and seeing more is the same thing as understanding more. This belief marks the age-old collision point between science and philosophy.

In earlier times, philosophy was displaced by the hope that the ability to understand could be developed through meditation techniques and ‘looking inwards’. Since 1828, it has been displaced by the exclusive store set by technical development and research, ‘looking outwards’. In both cases the result is error: in earlier times, an excess of mystical, occult and magical theories; nowadays, an excess of technical, political, psychological and parapsychological theories.

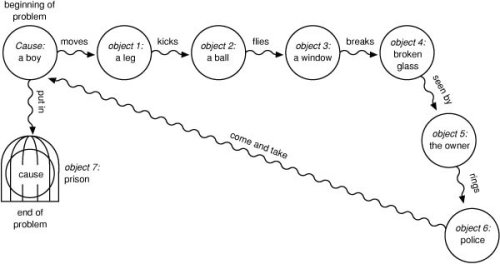

If we fail to take account of the relative nature of the senses, and instead base our view of causality on what our eyes see, thus binding our view of causality to time and space – i.e. leaving out of account the invisible reality behind our perishable reality – then we will understand causality and the functional* connection between everything in the following way (Diagram 2).

Diagram 2: A linear causal chain based on the sense of sight, bound to time and space, with relative and manipulable causes.

Click to enlarge

This basic view of causality locks us into the idea that everything is an object in itself, that there are only separate objects (which we consider to be either ‘living’ or ‘dead’ [see Dialogue 2, ‘“Life” and “death” vs conscious and non-conscious’, p.57]. We imagine that there are functions – such as going, flying, seeing, loving, or light, warmth, electricity, gravitation, etc. – that create between the separate objects relations or connections that are either temporary or stable.

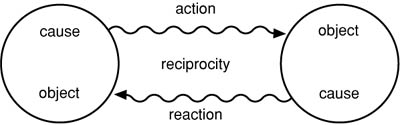

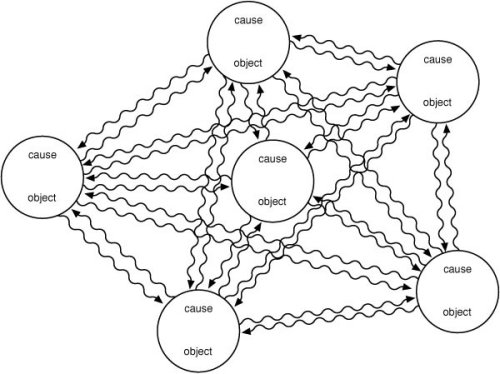

If we use this view to begin seriously looking for the real cause – that is, for the original cause – we cannot escape the problem that all the parts that we can distinguish as living or dead objects demonstrate some form of activity themselves. Over time, therefore, they show up as both passively acted-on objects and as actively operating causes (Diagram 3).

Diagram 3: Every object both is acted upon by, and acts upon, other objects

This raises the dualistic problem of reciprocity – action and reaction – and, the same problem multiplied, the pluralistic problem of everything acting on and reacting to everything else. This makes the whole question of causality and truth relative. It also leads to an extremely complicated, frightening and irrational chaos (Diagram 4).

Diagram 4: Chaotic, relative, dualistic/pluralistic view of causality.

Click to enlarge

In order to avoid confusion, and in order not to be panicked by the feeling of helplessness engendered by this view of the question of causality, everyone’s psychological instinct for self-preservation forces them to carefully restrict their efforts at understanding. They explore only certain causal connections, and completely ignore or exclude others. They are forced to prioritize and specialize. From individually selected causes, so-called viewpoints, they develop explanations that explain nothing about the philosophical question of cause – that is, the single, original, absolute cause.

Distinguishing between philosophy and technology

Distinguishing between philosophy and technology

All of us can readily understand what philosophy and the human characteristic connected with it are. We just need to keep in mind that the senses are limited, and to realize that the evaluation of the question of causality that we make on the basis of sight and the comparative thinking connected with sight represents only one type of objectivity. The natural purpose of this type of distance-based objectivity – technological objectivity – is the development of our ability to act.

Then we need only to allow the logic that we all used in childhood to be valid. This is the purely life-based objectivity that children have before they are confused by what they are taught about human identity. And by ‘life-based’ is meant that it is based entirely on both our immediate - subjective - and our distance-based - objective - experience of life. The natural purpose of this pure human logic is to understand the objective cause and meaning of the whole of life.

Since the time when, with the development of modern science, it became humanity’s goal to actually find the original cause in the manifold – as some original, indestructible part [see references to Democritus in the Dialogues] – technological and philosophical objectivity have become completely mixed up. That is why it can seem very difficult at first to distinguish between the two. To do that we must discard what we have been taught, and go by what we built our logic on in childhood and which we still experience as the self-evident – that is, all the natural insights that arise out of our own experience of existence.

If we want understanding and communication between people to grow, so that we can put a stop to people’s increasing isolation, we must collectively renew an interest in the self-evident. We must build up philosophy alongside technological understanding. This requires us to stop ignoring or being irritated by the self-evident – which are our present ways of dealing with it, because of the one-sided interest in the learnable and the complicated to which we have been accustomed since childhood.

The ABC of philosophy

The ABC of philosophy

Philosophy has been put to use in every century because humans have always understood that they cannot see the source or cause of either themselves or everything they see around them. It was realized that everything we can perceive with our senses is changeable and destructible, and that something changeable, destructible and impermanent cannot be that cause. No permanent understanding can be built on the impermanent.

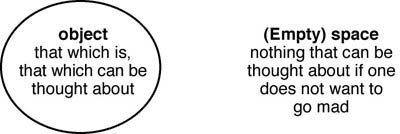

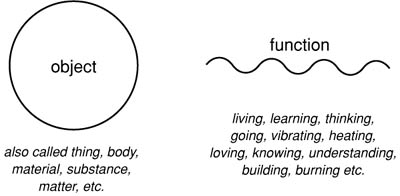

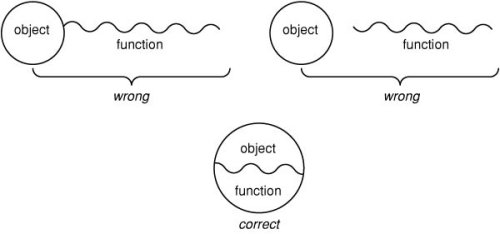

Proper philosophy must begin, therefore, by adopting a commonsense*-based stance as to what an object – that is, something permanent – is, and as to what therefore objectivity is. The term ‘objectivity’ derives from the fact that our whole experience of reality is founded on experiences of objects and functions (Diagram 5).

Diagram 5: Object and function

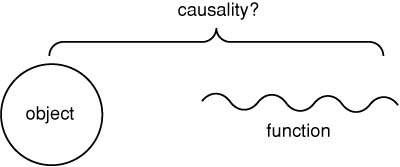

It is self-evident to every ‘child-mind’* – that is, to a mind not confused by purely language-based ideas – that for a function to be able to arise, there must exist an object, a permanent something. In other words, a function, i.e. activity, cannot exist by itself, but only in conjunction with an object that functions, i.e. is active. This self-evident insight explains why we have problems understanding causality if, on the basis of our senses or our memory, we experience functions – for example, a sound, a smell, a feeling or an idea, or more ‘tangible’ functions such as lightning, smoke or a cloud – as detached ‘objects’ in themselves, without knowing where they come from (Diagram 6).

This creates the insecurity and anxiety we feel until we discover the cause of any function. To discover the cause of a function is what ‘to satisfy our understanding’ means. But if we content ourselves with surface, mechanical, sensory-based explanations – which means understanding based on impermanent causes – we gain only an illusory understanding and an illusory feeling of security. We then live in the belief that we have understood, but we cannot escape the problem that our understanding is superficial and does not ultimately satisfy us.

Diagram 6: Causality is incomprehensible if an object and its function are detached

If no interest is then taken in philosophy – in understanding the permanent, original cause – the anxiety that stems from an unsatisfying understanding persists, and with it an intellectual impotence. This impotence drives people to want to discover more and more of the endless possibilities that mechanical understanding offers. But the problem still cannot be escaped that all mechanical causal explanations bind understanding to the same impermanent, changeable image of reality.

This is how things stand nowadays. We should be aware, therefore, of the ‘A’ of philosophy: the self-evident, but easily forgotten, insight that only what corresponds to our conception of an unchangeable, permanent object – something that we cannot find in our visible image of the world, where everything changes and renews itself – can have existence, can be something. A philosophically conceived unchangeable object may be able to change its form, but it can never become more or less, or become anything other than what it is (Diagram 7).

Diagram 7: An existent philosophical object, something, may be able to change its form, but can never become more or less or anything else.

Philosophically, the concept of ‘object’ is the exclusive alternative to – that is, the opposite of – the concept of ‘space’ or ‘empty space’. ‘Object’ is occupied space, reality, that which exists, that which is something. ‘Space’ is the theoretically conceived opposite of ‘object’ and corresponds to the concept ‘nothing’ (Diagram 8).

Philosophically considered, ‘object’ cannot stop being, disappear or become nothing. Nor can it start out of nothing to become something and then grow by becoming more ‘object’ out of nothing. Thus reality fundamentally must be one and the same permanent object – viewed as an inseparable relation between the whole and its parts – which is unchanged throughout time. It is not, however, like a dead, rigid object that cannot express any function. Rather it is like our experience of a mobile object, such as water or a living body, with a changeable, relative relationship between the parts, but without this changeability altering anything about the whole state of the object or the object’s unity (Diagram 9).

Diagram 9: Reality: an existent object, a whole with relation to its parts

Next we should be aware of the ‘B’ of philosophy: the self-evident, but easily forgotten, insight that function cannot exist by itself. Function cannot exist like an object, nor can it appear alongside or detached from the object that expresses the function – though we often believe the opposite when we do not take the relative nature of the senses into account (Diagram 10).

Diagram 10: The relationship between an object and its function

This is why it is futile for scientists to try and work out what movement, warmth, electricity and the other forms of energy are in themselves. Equally, it is impossible to find the explanation for life by trying to set our eyes on what life itself is – as impossible as discovering the function ‘walking’ in the absence of someone who is walking. Function can be the expression of an object only for as long as the object expresses and thereby sustains the function continuously in time.

The logical conclusion is that function must be conceived of as the expression of an object’s inherent, permanent nature – in philosophical terms, the ‘ability’ or ‘quality’ of an object. This means that a permanent, original object also has a permanent, original nature that is in no way changed by the object’s starting or ceasing to be active, that is, whether it is a temporarily active or a temporarily inactive object. (Diagram 11)

Diagram 11: On the left: An object, only conscious of itself, but otherwise inactive.

On the right: A creating object active in relation to its parts

For philosophy, though, it is necessary to understand the difference between two forms of activity. One is consciousness in itself, which is understandable if we know its need, that is, its intention. The other is the activity initiated by consciousness in order to satisfy the need in relation to the environment. The understanding of the first is a philosophical question, the understanding of the second is the natural purpose of memory-based thinking. (It is impossible to represent the relation between these two diagrammatically.)

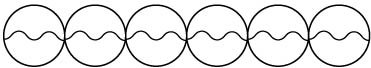

Next we should be aware of the ‘C’ of philosophy: the self-evident, but easily forgotten, insight that function, because it is not something in itself, cannot be transmitted from object to object except by direct contact. This is self-evident proof of the fact that in the whole reality the objective relation – between the whole and its parts – and the functional relation – what we call Nature – must be an unbreakable, permanent unity (Diagram 12).

Diagram 12: Function can be transmitted from object to object only by direct contact: thus the whole reality, including Nature, must represent a permanent unity

God and the conscious mind.

God and the conscious mind.

These self-evident philosophical reflections about the relationship between object and function were current in all old cultures. Thus people have always been convinced that there must exist at root a permanent, original object, and that the understanding of this object can explain all the changing phenomena that we experience with our senses. The same conviction also characterizes modern science, and explains why scientists search for this permanent, original object so feverishly.

In earlier times it was regarded as self-evident that this permanent object must at least have the same nature that we have. That is, it must be a living being that is conscious of itself. It is illogical to think that the cause of ourselves lacks the nature that we ourselves experience. So this philosophically conceived permanent object came to be interpreted as a human-like, living being, and acquired the name ‘God’.

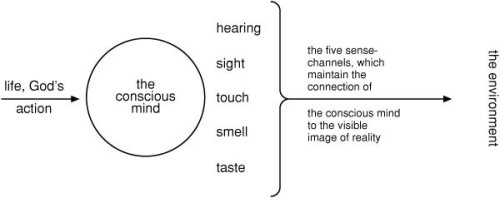

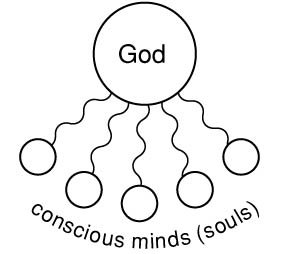

With the same philosophical objectivity, it was considered self-evident that there must also exist a permanent object that is the cause of what the changeable form of each human body expresses. This object was called the conscious mind, and was thought of as a unitary sense behind the five sense-channels (Diagram 13). This term for the human being’s permanent identity fell away in the Christian tradition, and is only hinted at in the functional concept ‘soul’.

Diagram 13: The place of the conscious mind in relation to God, the senses and the environment

Click to enlarge

Because of the lack of technical knowledge of the surrounding image of reality, religions constantly made the same mistake when interpreting the relationship between God and the conscious minds. They began from the limited experience that sight gives of relations between objects in the surroundings, and so imagined God alongside the conscious minds (souls), with functions acting as the links (Diagram 14).

Diagram 14: The mistaken view of God's relationship to the conscious minds

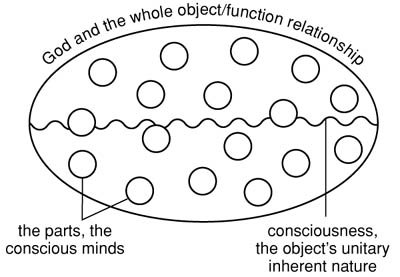

The organic view of unity aims to correct the faulty conception shown on Diagram 14 by combining philosophical objectivity with the knowledge of our image of reality that modern science gives.

If we allow philosophical objectivity to be valid, it becomes quite self-evident that everything that the whole reality expresses must have a permanent, living cause – God – and that what our life expresses must also have a permanent, living cause – the conscious mind [or what Hlatky later always referred to as 'part'. Ed.].

Viewed logically, the relationship in fact must be an objective relationship between an indivisible whole, which is living, active and mobile within itself, and its parts. There must be an indivisible inherent nature that holds both for the whole object and for all the parts in it (Diagram 15).

Diagram 15: Organic view of unity's view of the relation between God, the parts and consciousness

To use a modern comparison, we can think of the whole reality as a living organism in which we as conscious minds [parts] inhere as parts, in a way that is similar to the way cells inhere as parts in our living body. The fact that we, in our capacity as conscious minds [parts], are parts of reality’s invisible permanent existence – the whole object – means that we cannot see or touch either the object that we are or the whole object. All attempts in this direction are simply a waste of time, and they block our understanding by involving our brains in clearly irrational issues. The fact that we cannot see or touch the object itself does not prevent us from understanding what is essential about the object: its inherent nature or essence, that which we ourselves experience – that is, our ability to experience.

We experience this – God’s and our nature or essence – expressed in several ways. We experience it in relation to God as the active, superordinate, unitary Nature of the whole universe. We also experience it as ‘an expression of life’: this occurs when we see – that is, indirectly experience with our sight – the expression of another conscious mind [part]. Finally, we experience it as our own consciousness, our own awareness, our own experience of being. This last is our primary, direct experience of the nature that we have in common with God.

If we base a discussion of the object-question on these experiences, and bear in mind our common dependence on Nature, we can begin to understand ourselves and the common reality in which we live. We can never experience any other nature or quality of the original reality, which includes ourselves, than consciousness. Certainly we can theoretically conceive of the opposite of being conscious: being dead – because we see ‘dead’ animals and ‘dead’ human beings and we generally think of the whole universe as ‘dead’, that is, as not having consciousness behind it. But we cannot experience this opposite state.

Scientific research offers evidence

Scientific research offers evidence

The organic view of unity takes into account the philosophical significance of scientific research. This was not possible in philosophical discussions of the past. It became possible when the age-old philosophical idea that the senses are limited was confirmed experimentally with the help of technical instruments, and the law of energy was formulated.

The law of energy, simply put, states that matter is energy (Einstein’s E=mc2). Interpreted philosophically, this means that what we experience, on the basis of our senses of sight and touch, as objects and causes are not objects and causes in the philosophical sense, but energy or function.

In films or television and, most recently, in lasers, technology has given us analogies to this that we can actually experience. Here functional phenomena are experienced as convincing realities, in a similar way to the way we experience things in reality itself. The whole experience that we have watching a film at the cinema is a sense- and memory-induced ‘dream’, provoked by the phenomenon of light on the cinema-screen. A similar illusion occurs, even without the cinema, when we day-dream.

Part of the reason that we have not noticed the philosophical significance of the law of energy is that the whole of our upbringing and education is based on the belief that all the objects that exist are to be seen in the image of the universe. In addition, it is generally considered that as individuals we can see only a microscopic part of the total function compared with what all the experts together can see, which in turn is only a microscopic part of all the invisible function that exists. So it is considered quite pointless even to try to adopt a stance on the basis of the little that one individual can see.

We should turn around this disempowering view of the situation. We should realize – basing our view on the true significance of the law of energy – that we can easily conceive of the object (God), even though we can never set our eyes on it. In addition, we are all fully conscious of the function that we need to take into account in order to understand ourselves and the whole reality.

Thanks to the success of scientists in literally seeing through our whole image of reality without finding anything permanent in it, we can nowadays apply philosophy in an objectively anchored belief in God and in an objectively anchored belief about ourselves. We can thereby begin to develop a common understanding of objects and function, both visible and invisible, in the whole reality.

We need schools and research in order to learn how to act purposefully in the world. We need philosophy in order to be able to apply correctly – while constantly remaining conscious of the Nature to which we are all bound – what we learn in schools and through the discoveries of research.

Experience of life nowadays

Experience of life nowadays

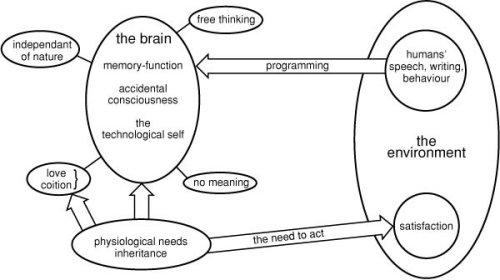

That the human sciences – psychology, education and sociology – are so fragmented that each person nowadays has a different theory is because, locked into the sense of sight, we localize consciousness in the brain, i.e. in the function of memory. We start from the idea that consciousness arises gradually in the brain, projected there by impressions from the environment – though also influenced, of course, by physiological needs and genetic inheritance. This view is represented diagrammatically in Diagram 16.

Diagram 16: The modern scientific conception of the human being and his/her relation to the environment.

Click to enlarge

Children, therefore, never acquire a conception of their true identity. Locked into a one-sided belief that the environment – especially in the form of our own species – makes the child what it is, they try on that basis to work with their ‘consciousness’ to acquire a better identity. This operates like a closed loop that constantly confirms the theory and locks them into it more and more: that is, they try to influence their environment, especially their relationships with other people, so as to acquire a better identity for themselves, so as to be able to improve their environment further, so as to be able to acquire an even better identity, and so on. Added to this are the dubious and confusing theories suggesting, for example:

1. that we have freedom of thought;

2. that we can change reality, and are on the point of freeing ourselves from Nature as a result of learning to control it;

3. that there is, therefore, no defined meaning to life, but only those meanings that we ourselves invent;

4. that love begins when one falls in love with somebody;

5. that expanding one’s consciousness means either broadening one’s conception of what one’s environment is, or doing research and increasing one’s knowledge of a limited environment.

If we are brought up with the idea of a fundamentally dead reality, the interest in an unlimited consciousness of the whole cannot even arise. So we have a situation in which trained scientists, trying to understand in its entirety this reality that they think of as dead, completely restrict themselves to the sense of sight and spend thirty or more years studying in order to be able to see what can be seen only inside scientific institutions. Those who lack this opportunity cannot think of anything to do other than to ignore the question of causality and to wait until the scientists have solved it.

Experience of life in the future

Experience of life in the future

We need to persuade those who manage our mass media to become interested in ending the present culture-war by initiating a general exchange of opinion on the basic, age-old philosophical concepts of

(1) God, the living cause

(2) the conscious mind [part], the human being

(3) the soul, the personality.

This exchange should start from objectively considered ideas and should take the relativity of the senses into account. Then the whole question of causality and the human sciences could both be rapidly enlivened again.

What is required is that we collectively realise that a philosophically convincing belief in God is the natural state of every human being. If we have a philosophically convincing belief in God, then we experience our true human identity. Such a belief is also a prerequisite for our being able to understand one another when we talk together about conditions in reality. This ability animals do not have. If there is no interest in the cause and meaning of conditions in reality, then each person spontaneously, from early childhood, wants to experience him- or herself as the cause, even though we know that this cannot be right. This gives rise to the double identity – that is, an acquired identity superimposed on the natural identity – which blocks understanding, communication and agreement, as well as the benefit of love that accompanies these.

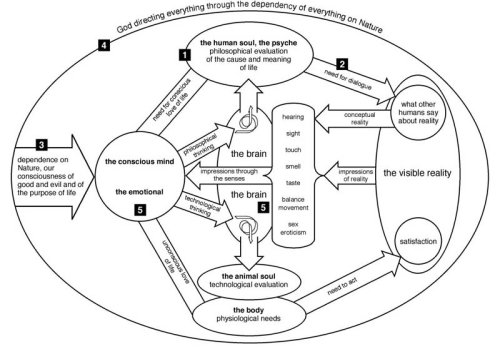

Diagram 17: The organic view of unity's conception of God, the human being, the environment and their interrelations. (The numbered sets of questions in the text relate to the numbered areas in the diagram.)

Click to enlarge

Diagram 17 seeks to highlight how the evaluation of the human being’s experience of existence is changed by a living, organic view of unity, and what general questions this raises.

1. (See relevant area of Diagram 17)

Is it sensible to believe that conceptual reality is a reality separate from Nature; in other words, that human beings can have their own reality, alongside the reality in which we all live?

What does ‘to torment one another psychologically’ mean?

Do not all mental troubles arise out of fixations on ideas?

Why do we become fixated on ideas?

Which Nature is superordinate: our conceptual reality, or the Nature that rules in reality?

What are the consequences if each person has their own unique reality disconnected from Nature?

What is the difference between day-dreaming and involvement in reality?

How can it be possible to do violence to each other with words, i.e. combinations of sounds?

2. (See relevant area of Diagram 17)

Animals cannot speak to each other about Nature, but humans can. What is meant by ‘idea’?

What kinds of ideas do we create in children’s Nature-conscious minds when we teach them to talk?

There are many languages, but can we, with respect to meaning, invent any language we like?

Is it not in fact Nature that governs language?

Do we gain anything by ignoring the fact that Nature governs language?

Why do we need to talk to each other?

3. (See relevant area of Diagram 17)

Is it the brain – the data-machine – that determines how Nature should be?

Does not everyone know that Nature is determined?

Do we have an undetermined freedom to think about the determinedness of Nature in any way we like, or is it a freedom with responsibility?

Is the determinedness of Nature altered by our thinking any way we like?

Who starts to suffer and to become disturbed when we think mistakenly: Nature or we ourselves?

4. (See relevant area of Diagram 17)

Can we conceive of the whole reality if we do not conceive of it as one?

When do we begin to conceive of something as one?

Do we think about the human being when we think about all the parts of the human body?

Do we not have to give a name to everything we want to talk about?

Is it plausible to conceive of the whole reality as a mechanical function?

Can any mechanical function first create itself with the fantastic, purposeful precision that the construction of the whole reality displays, and then also make that intelligent being, the human, who is supposed to direct reality?

5. (See relevant area of Diagram 17)

Is it plausible to think that the brain, which has been shown to be a biologically constructed data-machine, can programme and direct itself?

Why, then, does everyone speak of the heart in relation to being touched emotionally, without anyone thinking of the pump that keeps the blood in circulation?

Is there any reason to think and strain one’s brain if one considers that everything is as it should be?

We have built up an enormously fine medical system for caring for the body. Why does everyone complain that the person has been neglected? Who has done the neglecting of the person?